5 lessons I learned over 20 years of consulting on the "Idea VS Execution" debate

An idea’s brilliance is not innate but it is revealed by the way it is implemented.

Hello to the 2,960 subscribers who read Consulting Intel!

When I was younger, I thought intelligence was about having good ideas.

The better the idea, the smarter the person. I believed that if I thought hard enough, analyzed deeply enough and pictured every possible detail, I could bridge the gap between theory and reality.

I actually believed that all the answers were in my head, waiting to be unlocked.

It took years, and more than a few humbling experiences, to realize that this belief was, well, complete bullshit.

Someone, perhaps Yogi Berra, once said: “In theory there is no difference between theory and practice - in practice there is”, and that quote will stay with me forever because it so perfectly captures the gap between the clean world of ideas and the messy world of execution.

In the business world, there has always been a debate: what matters more, the idea or the execution?

At first glance, it feels like a balanced argument: both are essential. A bad idea, no matter how well executed, will fail, and a brilliant idea, poorly executed, is nothing but wasted potential.

This framing is overly simplistic because execution is where the real weight lies.

Even the most dazzling ideas are fragile: they rarely survive first contact with reality in their original form and their true value is only uncovered during execution.

This is the hard truth I did not grasp early on:

An idea’s brilliance is not innate but it is revealed by the way it is implemented.

To explain this, I often think about my soccer life.

Years ago, when I had a head full of hair and was fitter, I had plenty of great ideas on the pitch: quick passes, clever moves, Ronaldo-like feints, majestically executed shots, and more. Back then, I could actually act on (most of) them.

Today, those ideas are still vivid in my head, but my body cannot execute them. The game does not care how good my ideas are if I cannot follow through.

It is the same in business: no matter how sharp or innovative your idea, it is execution that determines whether it thrives or fizzles out.

20 years ago, Derek Sivers wrote a sharp piece on this, framing ideas and execution as factors in a multiplication equation. I largely agree with his perspective, but I would argue that execution deserves a disproportionate weight in that equation.

Over time, I noticed something peculiar about how people approach ideas, especially in business and consulting. There is this almost romantic belief that if you do enough research, run enough analysis, assign pseudo-probabilities to outcomes (of course, all subjective!), and rely on so-called “best practices”, you can insulate yourself from failure.

It is as if wrapping an idea in layers of preparation will guarantee its success when it hits the real world.

Consultants, in particular, are prone to this.

I have seen it countless times: people spend years doing spreadsheets and PowerPoint decks, crafting models that look flawless on paper, and not enough time in the trenches, dealing with the messy, unpredictable realities of implementation.

The result is often a beautifully crafted plan that crumbles the moment it encounters the chaos of execution.

To clarify, when I talk about an “idea” here, I am not referring to the obvious, everyday kind of ideas - like remembering to take an umbrella and dress appropriately when it is raining. That is common sense. I am talking about ideas in complex, dynamic systems, where success depends on countless interconnected factors and where the unknowns vastly outweigh the knowns.

Ideas like launching Uber (“Let a stranger take you for a ride in a city you do not know”) or Airbnb (“Sleep in a stranger’s home in a city you have never been to”) on paper sound risky, even absurd. In execution, they redefined industries.

Here is the problem: a priori, identifying a truly “good” idea is almost impossible because the world operates within a framework of randomness.

In complex systems, early decisions often create path dependence. This means that initial choices, however small, can snowball and significantly influence long-term outcomes. A slightly different choice during execution - say, targeting one market segment over another or choosing a certain operating model - can lead to dramatically different results. The randomness of these early decisions adds to the unpredictability of an idea’s success.

For instance, Uber’s initial focus on premium black car services could have locked them into a niche market if not for their pivot to a broader audience.

Their success was not baked into the idea itself but rather in how the team responded to early feedback and made choices that set them on a winning trajectory.

Consumer preferences and competitive landscapes are constantly shifting. What seems like a brilliant idea today could be irrelevant tomorrow because market conditions change faster than you can plan for them, and an innovative product or service is only as good as the market’s willingness to adopt it.

Competitors can emerge unexpectedly, consumer needs can evolve, and external factors (e.g., regulatory changes or economic downturns) can derail even the most promising ideas.

Again, take Airbnb, for example. When they started, the idea of staying in a stranger’s house sounded bizarre, but economic conditions during the 2008 financial crisis created a moment where people were more open to saving money by renting out spare rooms. Without those specific market dynamics, Airbnb’s idea might have gone nowhere.

Success in complex systems often depends on external factors like timing, adoption curves and network effects.

For some ideas to succeed, they need a critical mass of users or participants. Timing plays a very important role here: being too early or too late can make all the difference.

For example, social media platforms like MySpace and Friendster had the right idea but were either too early or lacked the execution to capitalize on network effects.

Facebook, on the other hand, entered the scene at the perfect moment, with the right execution strategy to attract users and create a self-sustaining network.

This is where execution rises above ideas.

A skilled execution team understands that success often requires iteration, pivots, and tight feedback loops. They do not cling to the original idea like a sacred relic, instead, they test, learn, and adjust in response to the randomness, market dynamics, and external forces that no amount of upfront analysis can predict.

Being agile (a terminology that has been stripped of its core meaning in the last 15 years) means being willing to abandon your initial assumptions and make course corrections based on what reality is telling you. The best ideas are often unrecognizable by the time they succeed because execution molded them into something entirely different.

Note that this is not a failure of strategy: it is the very essence of success in complex systems.

In business, as in life, most experiments fail. That is okay.

I argue that progress comes not from dreaming up flawless ideas but from refining imperfect ones: the world does not really reward the person with the best plan on paper but the team that can take an untested idea and make it work in the wild.

When you zoom out and take stock of all this - the balance between ideas and execution, the unpredictability of complex systems, the role of randomness, and the adaptability required to navigate it all - 5 clear lessons emerge:

Do not fall in love with your idea.

As I mentioned already, ideas are fragile, often incomplete sketches of reality. They are starting points, not endgames.

The moment you start treating an idea as sacred, you risk losing sight of what actually works.

Fall in love with the process.

Testing, refining, discarding what does not work, doubling down on what does: this is the way.

Execution is a constant feedback loop between what you thought would happen and what actually does. This is where value is created: not in the brainstorming session, but in the weeks, months, or years of trial and error that follow.

Embrace failure as a feature, not a bug.

Too many people are paralyzed by the fear of getting it wrong, as if failure is the enemy. Failure is not a sign of incompetence but a proof that you are trying.

The important thing is not to avoid failure altogether - which is impossible - but to structure your execution so that failures are small, manageable and, most importantly, instructive. Each failed experiment is a data point that brings you closer to the truth.

Take an incremental approach to execution.

Forget about perfect plans and grand launches. Start small. Build a barebones prototype. Put it out there. See how the market reacts. Listen to the feedback, iterate, and improve. Over time, what started as a rough idea will evolve into something far more refined and resilient. This approach is the closest thing we have to an antidote to the randomness of complex systems.

Understand and respect the role of luck and timing.

It is easy to look at successful businesses or leaders and credit their brilliance, their strategies or their vision. While those things all matter, let us not underestimate the role of sheer dumb luck.

The right idea at the wrong time will fail.

The right idea with poor execution will also fail.

The world is messy, unpredictable and unfair, and sometimes, the only thing that separates success from failure is a roll of the dice.

The good news is that luck favors the prepared. The more you execute, the more shots you take, the better your chances of being in the right place at the right time.

So, maybe this is the ultimate truth about ideas and execution: execution is about doing but also about learning.

It is about being humble enough to admit that your idea might be flawed, curious enough to explore alternatives, and thick-skinned enough to keep persevering when things do not go according to plan. Because they rarely do.

Ideas are the spark, but execution is the engine. And if you want to go anywhere, you need both.

Ciao, until next time! 👋

✍ The Management Consultant

PS: If you like this newsletter, I have one huge favor to ask.

Share it around with friends, family and colleagues.

This is the most effective way to support me (…and to keep me motivated to continue writing 😁).

Thank you 👇👇👇

🎯 INTERESTING SH*T

A couple of things I found on the internet that you may like…

I’m 99% sure you have bad neck posture so you have to read this:

Just watched this episode of Modern Wisdom and I think you should too:

🚨 SPONSORSHIP

Almost 3,000 consultants globally read Consulting Intel and rate it a 8.2/10 newsletter!

The readers include management consultants from McKinsey, BCG, Bain, Deloitte, EY, EY-Parthenon, KPMG, PwC, Accenture, Oliver Wyman, PA Consulting, and various boutique consultancies worldwide.

Many corporate employees and independent consultants are regular readers of Consulting Intel.

If you think your products or services could resonate with this audience, get in touch!

👀 JOIN THE DISCORD SERVER

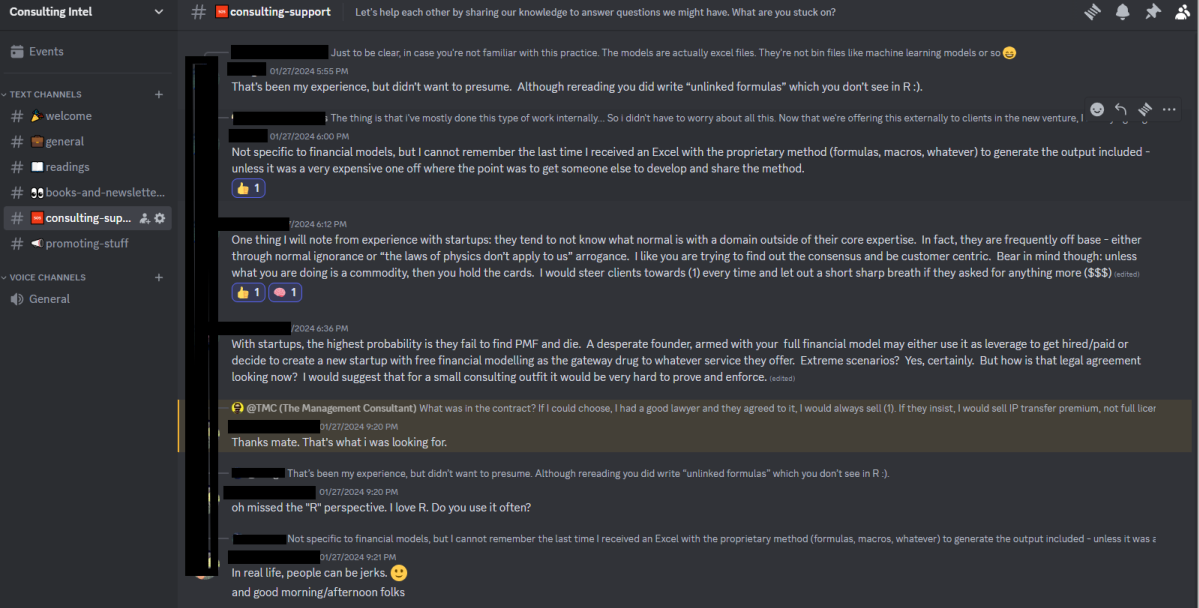

If you like this newsletter, you will love our Discord Server.

In there, you will find a tight-knit community of 170+ management consultants from all over the world discussing real-life challenges, giving each other support and recommending the good stuff to keep our knowledge top notch.

This is a massive part of the art of commercial creativity.

Agencies selling creative concepts and ideas to clients for big budgets - and the precarious journey to translating abstract stories and ideas in to execution

These days you hear a lot about AI making execution “cheap” and that the big thing now is the curation of ideas. While I appreciate that AI can massively speed up some of the iterations or learning cycles, it seems to me the points you make here will continue to be very relevant regardless of the execution tools.